Science Communication

Bone Flute is an art-research project that communicates ideas and concepts, and technological approaches and practices, including scientific topics. This communication is both in the story the object itself tells, and through how it is exhibited and contextualised.

These are some of the topics with which the artwork and exhibition engage.

01

Scanning and 3D-printing in medicine

These processes combined allow reaching inside the body and making parts of it tangible outside the patient, which is both practically useful, and spectacular.

02

Surgical simulations and pre-operative rehearsals

This is an area of practice with benefits for medical workers and patients, which makes use of physical models and materials, counter to the abstraction of screens.

03

The impact of automation on work

Emerging digital technologies threaten the quality of people’s work experience, and identifying where humans and machines can work together well is urgent.

04

Inequalities in access to healthcare

Health outcomes for patients are influenced by what types of processes they can access, and what the waiting time is for them.

05

Appropriate technology and low-cost design

This surgeon’s work is in making an existing approach accessible in public hospitals by making it low cost and appropriate to context.

06

Patient agency and technology choice

I made choices as a patient as to the type and extent of my treatment, in collaboration with my doctors, and I advocate this collaborative approach to healthcare.

When the surgeon I collaborated with on the project spoke at the opening of the exhibition AIAIA – Aesthetic Interventions in Artificial Intelligence in Africa, of which Bone Flute was the centre-piece, he had this to say about our work together:

“The most precious thing that I’ve got out of this collaboration so far, is learning a lot from you about how to communicate about my work. Because doctors would go: “Wow this is really cool. I segment DICOM images into 3D-printed models to rehearse my procedures” and audiences go “what’s he talking about?”. Ralph tells a story, and I’ve literally been taken along for the ride. I’ve learnt so much from you about how to communicate about my work, how to think about it, how to draw people in. I really appreciate that.”

Rudolph Venter

Orthopaedic surgeon at Stellenbosch University, South Africa

One of the ways in which the exhibition ‘drew people in’ was through the spectacular aspect of Bone Flute – the object is created by ‘extracting’ a bone from a living body, and making it into an instrument. We can talk about ‘spectacle’ in art as an attention-seeking mechanism: features of a work that arouse strong feelings in an audience – that thrill, fascinate, or even horrify.

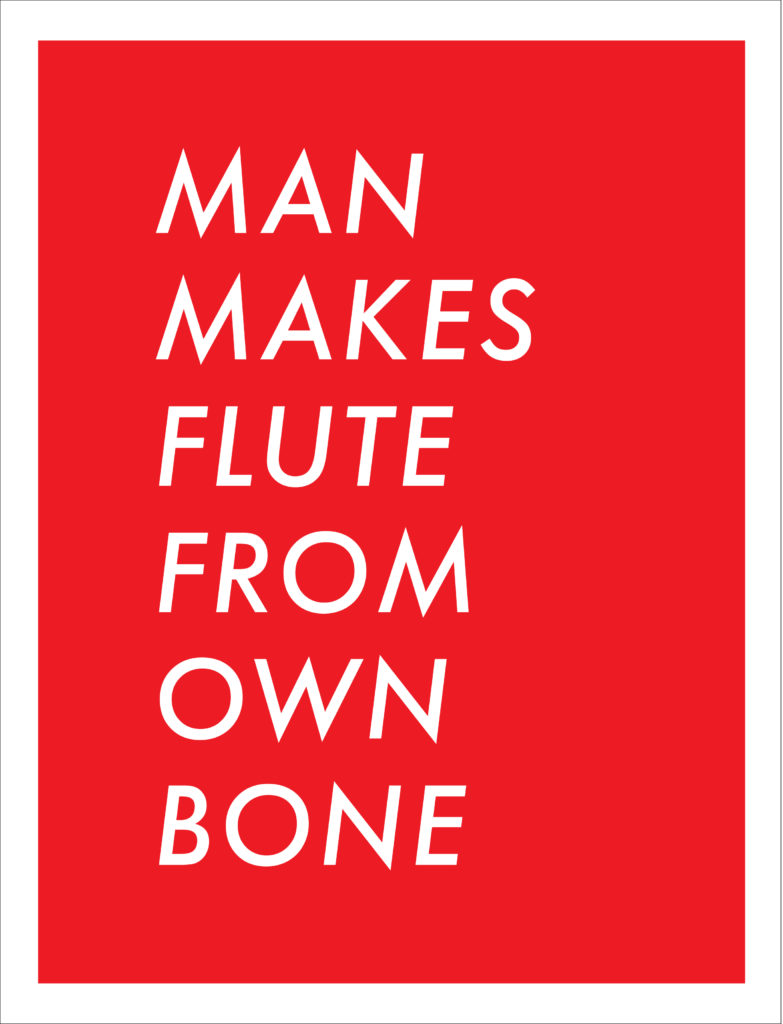

I designed a poster for exhibition near the object, that expresses this spectacular or attention-seeking aspect of the project. It’s in the form of a tabloid newspaper-headline placard, of the type that go up in the streets of South African cities every morning. It’s a deliberate elision of how the work is made, suggesting something macabre and very out-of-the-ordinary.

The mechanism here is to direct attention to a medical technology in use in a local public hospital which is in fact pretty spectacular – using medical scanning and 3D-printing, surgeons can make visible hidden parts of the body, previewing them and practising surgeries on them outside of the patient’s body, without harming the patient. My artwork distills this action down to the extraction and instrumentalisation.

From early on in conceiving this art-research project project, I wanted to ‘write my own headline’ for it, to make it attractive as a story to be taken up by media platforms and carried to wide audiences (because that is one way of increasing the impact of the work). That’s the idea captured in the tabloid poster artwork. And it has been taken up by at least one news platform so far: UCT News, my university newspaper, published a story on the project with the headline ‘Flute from his femur‘, which has a similar effect.

I brought Rudolph’s work into the exhibition in a more straightforward way too; on a table in the centre of the space were examples of 3D printed bones from his laboratory, and a few printed papers about his work. Audiences could sit on the two chairs next to the table, read more about his work, and examine the 3D-prints. This table was also used for conducting meetings and interviews with visitors during the exhibition run – my idea was to inhabit the space as a public laboratory, working there and engaging with visitors.

I was able to arouse the imagination of audiences around the flexible potential of software models and affordable 3D-printing, through collaborating with a colleague who works with medical scanning and printing, and was inspired to get involved. He brought his 3D-printer into the exhibition space and left it running, producing miniature versions of my femur that visitors could take away with them. This illustrated scalability of software 3D models (the ability to scale objects is something I’m fascinated by as a sculptor, and it does suggest a kind of ‘Alice in Wonderland’ type magic for audiences) and affordability of filament 3D-printing (a feature of Rudolph’s work at Tygerberg Hospital is that it is intended to be low cost to benefit public-healthcare settings).

In order to produce a digital 3D model of my femur from my medical scan, that could be printed, Rudolph had referred me to his collaborators at CranioTech, a private company that specialises in medical 3D-printing. We needed their expertise because the data from the MRI scan I’d received wasn’t complete enough in all areas – the ends of the bone were pretty good, but the shank of the bone wasn’t. The approach CranioTech took was to use a process called statistical shape-modelling, which uses algorithmic methods to draw from a large database of male femurs, and apply their shape to my femur, completing its missing parts in a way that corresponds to my anatomy. The irony here for my project is that it averages out part of my anatomy, rather than being 100% unique to me. A gain is that it brought an algorithmic process, one of the research areas in Future Hospitals, into my work.

One of the main ways in which I conveyed information to the public, such as the anecdote about statistical shape-modelling above, was through my live presentations in the exhibition. I did this at the opening and closing events of the exhibition, and at intervals over the two-week run. In Rudolph’s speech at the opening, which heads this page, he describes my ability to ‘tell a story’. Public-speaking is a mode which I enjoy and am comfortable with, engaging live with an audience. I designed the exhibition to support this, with objects, images and video which I could refer to in telling the story of the work; including picture rails – metal channels mounted to the walls – which contained image cards which could be added to and rearranged during the exhibition run, and potentially handled by visitors.

I thought about this as creating a real-life ‘memory palace’, those imaginary structures which ancient orators were supposed to have used to assist their public speaking on a topic, as they imagined walking through a space in their mind which contained objects and images representing key aspects of fields of knowledge. I could lead visitors – including journalists and potential work collaborators as well as the public – through the exhibition, using exhibits as touch points and examples to structure my story about the work.

The experience of staging this exhibition reminded me that there’s nothing quite like (in my experience) having a physical site for a fixed duration of time to engage other people with your work. It makes possible interactions with others, some of whom I may already know, but who don’t know what I’m working on currently, and have goods to offer the project, and people I don’t know, who are drawn to the project and offer information and resources because the material resonates with them. I use some of my past experience as a club promoter, as well as a curator, to create engaging experiences: inviting DJs to perform at the opening and closing events for example, playing sounds and music along the theme; and inviting interactions with musicians and other artists and researchers. It’s a fruitful way of doing things.

A thought about the work on this project, and art-science work more widely, is that I believe that the best work happens when the art has its own value as sensation, spectacle and intellectual provocation – that it’s not an illustration of a science idea; rather it points to areas of knowledge, catalysing deeper engagement with a topic. Learning how to follow my intuition as an artist, and to believe that what gives me pleasure as an artist will also yield results for research and communication to audiences, has come after decades of work – and has helped to unlock my process from only an ends-focused path to one that embraces process and recursive and incremental decision-making.