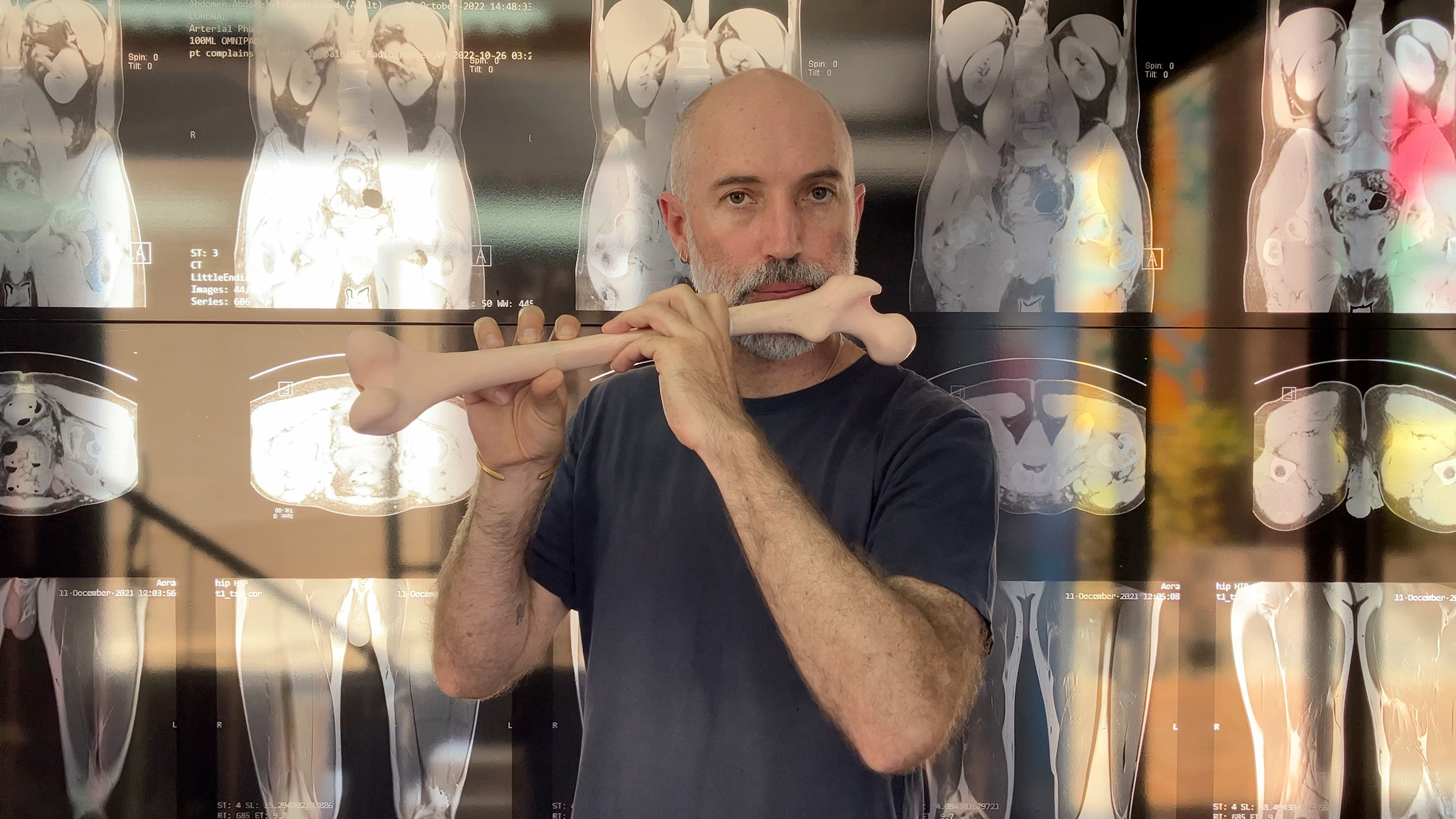

Bone Flute is a project to make a flute from a replica of my own femur, using medical imaging and computer-controlled fabrication.

I had my leg scanned in a hospital MRI machine, and a copy of my femur 3D-modelled and printed by a medical technology company. Holes for blowing and fingering the flute were drilled into the model in a simulated ‘operation’ in the same hospital, with my collaborators – an orthopaedic surgeon and a musician, and a filmmaker who produced a short film of the procedure.

The surgeon, Rudolph Venter, runs a medical 3D-printing lab at a public hospital in Cape Town. His work is in making more affordable processes for scanning and 3D-printing patients’ bones for the rehearsal of complex surgeries before an operation.

Practicing on life-size replicas of individual patients’ bones allows the surgeons to retain their embodied skills developed over years of experience – counter to the tendency of some automation technologies to deskill and disembody the worker.

The musician, Alessandro Gigli, is a classically-trained flautist and instrument maker, who has made reconstructions of historical flutes. My partner Dara Kell, a documentary filmmaker, produced a short film of our operation to make the flute. I am an artist-researcher whose work has often focused on the body, and the creative use of emerging technologies.

I undertook this work as a fellow on the Future Hospitals project, funded by the Carnegie Corporation, and hosted by HUMA, the Institute for Humanities in Africa at the University of Cape Town. The project directs critical attention to the “fusion between the human body, new technologies and the experience of being human”, investigating how new technologies, particularly those of the so-called ‘4th Industrial Revolution’ (such as AI, 3D-printing, and robotics) are changing the work of healthcare professionals in Africa.

I was interested in collaborating on a creative project which would allow me to find out more about the use of these technologies in the hospital and by healthcare workers such as Rudolph, while producing an object to stimulate public engagement with the topic. I’m particularly interested in my wider work in the potential for human- machine collaboration. The culmination of my fellowship was an exhibition, AIAIA – Aesthetic Interventions in Artificial Intelligence in Africa, of which Bone Flute was the centre-piece.

Woven through the exhibition was my own personal experience of the hospital, as I experienced injury and illness as a patient over the period of my research fellowship – from the hip injury which allowed me to have my leg scanned, to a cancer diagnosis – exposing me to the use of medical technologies for my own treatment.

At the time cancer was detected in my body, my partner was four months pregnant with our first child, my son Ira. My first sight of him was as a skeleton, cross-sectioned by the obstetrician’s ultrasound device, floating within a white nimbus of his flesh in the inky black of her screen.

I’d put myself forward for a cancer screening because I was the same age as my grandfather was when he died of the same illness, when my father was still a child. The detection and further investigation of my condition enabled by new imaging technologies, (as well as keyhole surgery and chemotherapy) may have made the difference to my being able to greet my own son at his birth, and to now see him to adulthood – that and the fact that I had recently switched to private health insurance, from public, and so there was no delay in receiving the immediate treatment I needed.

I intended Bone Flute as a memento mori, playing on a rich history of European imagery which (along with the danse macabre, at a time when plagues were sweeping the continent) reminded viewers of the presence of death in life – imagery which persists in popular culture: from Metropolis to Disney’s The Skeleton Dance.

Flutes and other musical instruments made from human bone are found around the world and across time, as part of widespread practices in which the dead (both loved ones and enemies or outcasts) are remembered and reanimated by touch and breath.

Normally one would have to be dead to have a tune played on your bone; the conceit of this artwork is that through new medical technologies for scanning, modelling and fabrication, intended for surgical simulation, the bone can be copied and reproduced outside of a living body – as if extracted from it.

It was by chance that my own mortality came into focus while I was developing the piece – and that working on the project came to help me through my treatment and recovery.

Future plans for the project include developing an automaton to play my bone flute; expanding the exhibition that surrounds it; devising a multimedia performance; and pursuing further writing. This writing includes the art, science and technology in which the project is immersed, as well as the threads of personal experience and family history which insinuated themselves into the narrative.

Science Communication

“The most precious thing that I’ve got out of this collaboration so far, is learning a lot from you about how to communicate about my work. Because doctors would go: “Wow this is really cool. I segment DICOM images into 3D-printed models to rehearse my procedures” and audiences go “what’s he talking about?”. Ralph tells a story, and I’ve literally been taken along for the ride. I’ve learnt so much from you about how to communicate about my work, how to think about it, how to draw people in. I really appreciate that.”

Rudolph Venter, Orthopaedic surgeon and project collaborator

Bone Flute engages in Science Communication, conveying technical subjects to non-technical audiences (as well as specialists across disciplines) in compelling ways. These are some of the topics that the project engages with.

01

Scanning and 3D-printing in medicine

These processes combined allow reaching inside the body and making parts of it tangible outside the patient, which is both practically useful, and spectacular.

02

Surgical simulations and pre-operative rehearsals

This is an area of practice with benefits for medical workers and patients, which makes use of physical models and materials, counter to the abstraction of screens.

03

The impact of automation on work

Emerging digital technologies threaten the quality of people’s work experience, and identifying where humans and machines can work together well is urgent.

04

Inequalities in access to healthcare

Health outcomes for patients are influenced by what types of processes they can access, and what the waiting time is for them.

05

Appropriate technology and low-cost design

This surgeon’s work is in making an existing approach accessible in public hospitals by making it low cost and appropriate to context.

06

Patient agency and technology choice

I made choices as a patient as to the type and extent of my treatment, in collaboration with my doctors, and I advocate this collaborative approach to healthcare.